Georgia O'Keeffe

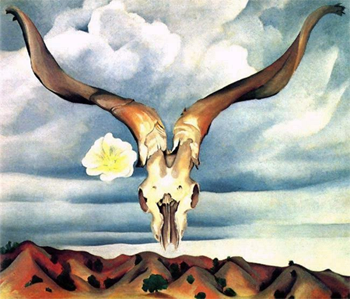

Easily recognized, Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings have a style all her own. The most familiar are her trade- mark paintings of large flowers, encompassing an entire canvas. She produced more than a hundred flower paintings such as "Black Iris" (1926) and "Red Poppy" (1927). Her other trade-mark motifs were white skulls and desert landscapes. O'Keefe focused on nature and rarely painted living creatures or people. Her later years, living in New Mexico gave O'Keeffe the time and the opportunity to become the master translator of the arid desert's exotic terrain.

Easily recognized, Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings have a style all her own. The most familiar are her trade- mark paintings of large flowers, encompassing an entire canvas. She produced more than a hundred flower paintings such as "Black Iris" (1926) and "Red Poppy" (1927). Her other trade-mark motifs were white skulls and desert landscapes. O'Keefe focused on nature and rarely painted living creatures or people. Her later years, living in New Mexico gave O'Keeffe the time and the opportunity to become the master translator of the arid desert's exotic terrain.

An aptitude for art had surfaced early in her childhood. The second of seven children, she was born on November 15,1887, and grew up on a farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Raised in the country, she and her siblings took art classes at home. Georgia's talent was recognized early and encouraged. By the time she graduated from high school in 1905, she was determined to be an artist. Attending the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as The Art Student's League, in New York City, O'Keeffe was trained in "imitative realism" – as were most art students of the time. Because of family financial problems, Georgia worked as a commercial artist for two years, and then for another two years taught drawing and penmanship in Texas.

By 1915 O'Keeffe attempted to find her own style and language in her art. She created a series of abstract charcoal drawings, representing what she said were her dreams and visions. She sent these pieces to a classmate, who on New Years Day 1916, showed the charcoals to Alfred Steiglitz, an internationally known art impresario and innovative photographer. Steiglitz later exhibited the drawings at his gallery, ignoring O'Keefees demands to end the show. The public was shocked by the perceived sexuality of the shapes, but O'Keefe all her life denied what other considered the Freudian symbolism inherent in her art. Stieglitz began a correspondence with O'Keeffe and in 1918 offered her financial support to paint for a year in New York. She moved there from Texas. At this time she had abandoned charcoal and had started using oils in vibrant colors. Georgia and Stieglitz fell in love and in 1924 were married. As early as the mid 1920's when O'Keeffe had begun her paintings of close ups of large-scale flowers, she was becoming recognized as one of America's most successful and important painters – due in large part to her continual promotion by Alfred. From their meeting, until his death in 1946, Stieglitz worked tirelessly to promote O'Keeffe and her work. His art gallery – 291 Gallery – known by its address on Fifth Avenue, was the launching point for modern art in the United States. Alfred Stieglitz, who was 23 older than O'Keefe has been called the most consequential evangelist for modern art and the avant-garde in the visual arts that the United States has ever had. Even today, it has been shown that Stieglitz had an unerring sense of radical beauty - at a time when the majority of American's had never seen a Picasso or Cezanne, and when traditional representative art was still the vogue. Both O'Keefe and Steiglitz were ahead of their time. Considered as the premier female artist of the 20th century – O'Keeffe considered that title - sexist. In his own right, Stieglitz still today is recognized as revolutionizing photographer. As a photographic chemist he achieved many technical successes with photography.

By 1915 O'Keeffe attempted to find her own style and language in her art. She created a series of abstract charcoal drawings, representing what she said were her dreams and visions. She sent these pieces to a classmate, who on New Years Day 1916, showed the charcoals to Alfred Steiglitz, an internationally known art impresario and innovative photographer. Steiglitz later exhibited the drawings at his gallery, ignoring O'Keefees demands to end the show. The public was shocked by the perceived sexuality of the shapes, but O'Keefe all her life denied what other considered the Freudian symbolism inherent in her art. Stieglitz began a correspondence with O'Keeffe and in 1918 offered her financial support to paint for a year in New York. She moved there from Texas. At this time she had abandoned charcoal and had started using oils in vibrant colors. Georgia and Stieglitz fell in love and in 1924 were married. As early as the mid 1920's when O'Keeffe had begun her paintings of close ups of large-scale flowers, she was becoming recognized as one of America's most successful and important painters – due in large part to her continual promotion by Alfred. From their meeting, until his death in 1946, Stieglitz worked tirelessly to promote O'Keeffe and her work. His art gallery – 291 Gallery – known by its address on Fifth Avenue, was the launching point for modern art in the United States. Alfred Stieglitz, who was 23 older than O'Keefe has been called the most consequential evangelist for modern art and the avant-garde in the visual arts that the United States has ever had. Even today, it has been shown that Stieglitz had an unerring sense of radical beauty - at a time when the majority of American's had never seen a Picasso or Cezanne, and when traditional representative art was still the vogue. Both O'Keefe and Steiglitz were ahead of their time. Considered as the premier female artist of the 20th century – O'Keeffe considered that title - sexist. In his own right, Stieglitz still today is recognized as revolutionizing photographer. As a photographic chemist he achieved many technical successes with photography.

Stieglitz died of a stroke in 1946. That year, O'Keeffe had been the first woman honored with a solo exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After Alfred's death, O'Keeffe spent the next two years settling his estate in New York. In 1949 she moved to New Mexico. She was in her early sixties and beginning a new life. From that time until her death she lived in the Southwest but kept her ties to the city and the avant-garde world. O'Keeffe considered herself an American artist, rather than a Southwestern artist. Finding people and society somewhat boring and superfluous, she preferred the isolation and solitude of her ranch, Ghost Ranch and her small house in Abiquiu. Georgia stated that once she had seen New Mexico, she had spent the next 20 years, "on her way back." She preferred a simple life – alone. Although some thought her testy and aloof, she preferred to keep her personal life private and to let her art speak for itself.

One of O'Keeffe's idiosyncrasies was not signing her paintings. She thought it detracted from the artwork itself. She also left the naming of her paintings up to others.

O'Keefe produced oil paintings until the mid-1970's when her failing eyesight forced her to abandon painting. She had begun to go blind at the age of 84 and eventually only retained peripheral vision. She completed her last un-assisted oil painting in 1972. In 1973, Juan Hamilton, a handsome young ceramic artist appeared at her door and offered his service as a handyman. For the remainder of her years, he was her controversial assistant and companion. In 1976, Juan encouraged and assisted her in publishing, "Georgia O'Keeffe." It is a best selling collection of her reproductions with her own text.

There was a resurgence of interest in O'Keeffe and her work. In 1977, President Ford presented her with the Medal of Freedom. A film portrait on public television also exposed her art to a wider audience. Her 90th birthday was celebrated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. With advancing age and failing eyesight, O'Keeffe worked in pencil, watercolor, and clay until her health failed in 1984. At that time she moved to Santa Fe to live with Juan Hamilton and his family. In 1985 she received the National Medal of Arts, from President Regan. She died in 1986. She was 98 years old. Her ashes were scattered over the countryside around Ghost Ranch, as she had requested. Most of her estate was left to Juan Hamilton, which caused a lawsuit by O'Keeffe's family. Hamilton turned over approximately two-thirds of the inheritance to the museums and institutions that had been named in her original will. In 1997, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum opened in Santa Fe. The museum's first exhibit curator was Juan Hamilton. Georgia O'Keeffe's art lives on after her - part abstract – part realistic – part East – part West – and definitely worth taking a closer look. If only because – her colors were incredible.